Our Philosophy of Care

At the University of Rochester Medical Center, we believe a kidney transplant is a lifelong commitment for you and for us. We will stay involved with you and your family through the entire transplant process. We get to know you very well and recognize that preparing for and living with a transplant will affect your lifestyle in many ways. We will help you maintain and resume many of your activities and even become involved in new ones.

We are committed to the time, effort, and resources required to make your transplant a success. And our definition of “success” extends far beyond the operating room. It means we’ll work with you to make your life after the transplant as successful as possible.

What Do the Kidneys Do?

The kidneys, a part of the urinary system, are a pair of bean shaped organs in the back of abdomen. They clean the body of excess water, salt and waste products. As blood circulates through the kidneys, it passes through more than a million tiny filtering units within them. These filters produce a liquid waste (urine). Urine flows from the kidneys through a pair of thin tubes, the ureters, to the bladder, where it is stored until a person urinates. The kidneys also produce important hormones that help regulate blood pressure, form bone, and control red blood cell production in bones.

Kidney Diseases

The two most common causes of kidney failure are diabetes and high blood pressure. If these two diseases are not well controlled over several years, the kidneys can ultimately fail and dialysis is then required. There are many other diseases that can lead to kidney failure. Some of the more common reasons for end stage renal disease requiring kidney transplant include: polycystic kidney disease, chronic reflux, glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy, and lupus.

These diseases, and others, can be treated in a number of ways. But if they have progressed far enough and the kidneys are damaged badly enough, and if other treatments have been unsuccessful, a kidney transplant may be the best treatment option. Your primary doctor will make the referral to the Division of Solid Organ Transplantation at the University of Rochester Medical Center.

What is a Kidney Transplant?

In a kidney transplant, a healthy kidney from another person is put into your body. This one new kidney takes over the work of your two failed kidneys. Kidneys may be donated by healthy individuals who are willing to bestow this amazing gift (living donor kidney transplant). Donors need not be related to the recipients, for example, good friends or spouses can be donors as long as they have a compatible blood type with the recipient and the recipient does not have any preformed antibodies against the donor’s tissues. Kidneys may also be donated from deceased individuals (deceased donor kidney transplant). These donors have either made clear their wish to become organ donors upon their death or their family members and loved ones have provided consent for organ donation when the donor dies.

Is a Kidney Transplant Right for You?

A kidney transplant is offered only to people who have irreversible, chronic kidney failure. Usually, other medical or surgical treatments have been tried before a transplant is considered. Age is not necessarily a factor in deciding if you’re a candidate for kidney transplant. Newborns, infants, children and adults past the age of 70 have all had successful kidney transplants.

What is important is your general health and suitability for major surgery. For example, you can’t have a transplant if you have:

- · Recent or active cancer

- · Serious heart, lung or nerve disease that would make the operation too risky

- · An active, severe infection that can’t be completely treated or cured, such as tuberculosis

- · An inability to follow your doctor’s instructions

To get your site onto good positions on results pages you’re going to need to learn about keywords, strategies for linking, white hat methods, things to avoid, things that can cause it. viagra no prescription The best thing about the this pill is that you will get the medicine effect lasting viagra france for more than 4 hours. It cialis 40 mg is certainly worried that almost 50% male over 45 are suffering from impotence epidemic. This will help the doctor decide on the time and the days when you would like https://regencygrandenursing.com/product4541.html order cialis online to remain sexually active, it’s of the essence which you preserve yourself healthy and fit.

Of course, all major surgery carries risks, and a transplant is no exception. The risks associated with surgery in general are:

- · Reactions to anesthesia

- · Problems breathing

- · Bleeding

- · Infection

Transplants carry additional problems, such as:

- · Rejection (the body considers the transplanted organ to be a “foreign substance” and uses its natural immune system to destroy it)

- · Life-long need to take medicines (called immunosuppressive drugs) that prevent rejection by suppressing the immune system; this weaken the body’s ability to fight infections and increases the risk of certain types of cancer

- · Finding a healthy organ

- · Cost

However, if your primary doctor recommends a transplant, it probably is the best treatment option for your condition. Kidney transplants do save lives.

If you’re referred to us for a kidney transplant, a five-step process will begin.

The Transplant Process

The information that follows is an edited version of a brochure about kidney transplants at URMC. You can request the complete brochure by calling us at 585-275-7753.

When you are referred to us for a kidney transplant, a five-step process will begin.

The Transplant Process – Evaluation

The first step in the transplant process is evaluation: the kidney transplant team evaluates your condition and decides if you’re a good candidate for a transplant. Our team includes:

Transplant surgeons

A kidney specialist

A psychiatrist

A social worker

Nutritionists

Nurses

Transplant coordinators

Other health care professionals

Usually within a week after you’re referred to us, a transplant coordinator will call you to discuss the evaluation process and set up your appointments. We’ll also do a preliminary financial and insurance coverage assessment.

Tests

For the evaluation, you’ll visit Strong Hospital twice, both times as an outpatient. During your first visit, you’ll have a number of diagnostic tests. You’ll have blood drawn and x-rays taken and you’ll be tested for blood type and other matching factors that determine whether your body will accept an available kidney. During the second visit, you’ll talk to the transplant team about your test results. (The second visit is usually a week or two after the first, but the whole evaluation process can be completed within 12-48 hours for a critically ill person.) We strongly urge you to bring one or two other people, who will become your support system, to all meetings.

Among other things, the tests will show if you have complications or conditions that might adversely affect your surgery. Cancer, a serious infection, or significant cardiovascular disease would make transplantation unlikely to succeed. In addition, the team will want to make sure that you can understand and follow the schedule for taking medicines. If problems are found, you may be referred to the appropriate specialists at Strong Health who can deal with them. You’ll also talk to a financial counselor about insurance and other ways covering the costs of the transplant and follow-up care.

Results

After the evaluation, the results are given to the Kidney Transplant Patient Evaluation and Selection Committee, which uses the Patient Selection Criteria and Implementation Plan to decide if you’re a suitable candidate for a kidney transplant.

If you don’t become a transplant candidate, the transplant team will support your primary care doctor, as appropriate, in managing your kidney disease. If you do become a candidate, you’ll be put on the waiting list for a donated kidney unless you have a living donor willing to donate a kidney to you. If you have a living donor, the transplant surgery can be scheduled immediately.

The Transplant Process – Waiting for an Organ

Unfortunately, there are many more people on the waiting list than there are organs available each year, so the wait can last up to several years. That’s why becoming an organ donor is so important.

National Waiting List

The national waiting list for donated organs is maintained by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). In 1984 Congress passed the National Organ Transplant Act to address the grave shortage of organs and improve organ matching and placement. The act set up the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) to maintain a national registry for organ matching. The network was to be run by a private, non-profit organization under federal contract. UNOS, the United Network for Organ Sharing, is that organization.

The network consists of many OPOs (Organ Procurement Organizations) across the country. Each is responsible for a specific region. For the Rochester, Syracuse and Finger Lakes region, the OPO is the Finger Lakes Donor Recovery Network (FLDRN). Affiliated with the University of Rochester Medical Center, FLDRN coordinates organ donation in 19 counties with a population of 2.4 million, and serves 44 hospitals in the Finger Lakes region, central and northern New York. The phone number is 585-272-4930.

Policies on Organ Donation

The UNOS and OPTN community includes medical professionals, patients, donors, their families and friends. Working together, the OPTN sets the policy on organ donation for the country, subject to approval by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). These policies are circulated for public comment and can be viewed at the UNOS Web site.

Livers are allocated based on the severity of illness. The sicker your liver is, the higher you are on the list. By contrast, kidneys are allocated based on the length of time a person has been on the wait list. The longer you’ve been waiting for a new kidney, the higher you are on the list. Only a few exceptions to these policies exist. For example, if a “perfect match” kidney (see below) becomes available, then it will be offered to you regardless of how long you have been waiting.

Matching Donor Organs to Recipients

The idea of needing a “perfect match” between the donor and recipient so that the organ does not reject is outdated. Current antirejection medicines are so effective in preventing and treating rejection that all that is required for a successful match is a compatible blood type and the absence of antibodies in the recipient directed toward the donor. Your blood type (A, B, AB, or O) must be compatible with the donor’s blood type. Also, for kidney and pancreas transplants, we test for the presence of antibodies (or proteins made by immune cells) in the recipient directed toward the donor. The presence of such antibodies can result in a severe, irreversible rejection, so transplants are not performed in this case.

A “perfect match” refers to a genetically identical (or nearly identical) donor and recipient pair. This is assessed by testing for HLAs, human leukocyte antigens, which are genetic markers located on the surface of your white blood cells. You inherit a set of three antigens from your mother and three from your father. If all six of these HLAs are the same between donor and recipient (which happens always with identical twins, 25% of the time with siblings, and extremely rarely between unrelated individuals), then the chances that your new kidney will last for a long time are higher. Anything less than a 6 out of 6 match does not statistically diminish the excellent outcomes of kidney transplantation, largely because of the efficacy of our current antirejection medicines.

While You Wait

While you’re on the wait list, you’ll have regular follow-up appointments with the transplant team and follow a set of important instructions. For example, you must tell us if:

You’re hospitalized

Your kidney condition worsens

Your address or telephone number changes

You lose insurance coverage

You travel out of town

There are any other changes that may affect your medical care

You need to have regular dental examinations and treat any tooth decay or other oral infections

You must be ready at all times to come to the hospital when called, and you can be called at any time for a transplant. Carry a pager or cell phone with you at all times. If you don’t have one, contact our office and we’ll assign you a pager. Also, you should continue to have regular appointments with your nephrologist or primary care physicians.

The Transplant Process – Transplant Surgery

You’ll be contacted when a kidney is available. If your new kidney is from a living donor, both you and the donor will be in surgery at the same time. One team of surgeons will do the nephrectomy (removing the kidney from the donor), while another prepares you to receive the donated kidney.

If your new kidney is from a person who has recently died, your surgery starts when it arrives at the hospital and the results of the cross-match test (looking for the presence of antibodies as described above) are negative.

The surgery can take from 3 to 4 hours or more. You will be given general anesthesia. Your surgeon makes an incision in your lower abdomen and puts the new kidney in place. Then the surgeon connects the artery and vein of the new kidney to your own artery and vein. Your blood will then flow through the new kidney. The ureter from the new kidney will be connected to your bladder. Often, the new kidney will start making urine as soon as your blood starts flowing through it, but sometimes a few weeks pass before it starts working. Unless they are causing problems, your own kidneys are left in place.

A Note on Deceased Organ Procurement

When a deceased organ becomes available, a team of surgeons and anesthesiologists removes it from the donor. Although the donor is brain dead, this procedure is treated like any other operation using standard surgical practices and sterile techniques. When the operation is complete and the incisions are closed, the donor’s body is prepared for funeral or cremation. Organ procurement surgery respects the body and an open casket funeral is possible if desired.

The Transplant Process – Recovery in the Hospital

You’ll probably stay in the hospital four days after surgery. Immediately after surgery, you’ll be taken to the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU). After an hour or so there, you’ll go to the Inpatient Transplant Unit where you’ll take medicines to prevent infections and rejection of your new kidney. Your doctor will examine you every day to make sure that your pain is well controlled, that the new kidney is functioning properly, and to monitor for any complications related to the surgery.

You’ll also be prepared for your return home. You’ll be given a schedule for follow-up visits and routine blood draws, and a 24-hour phone number for emergencies or other problems. You’ll learn how to deal with the medicines you’ll be taking and their side effects, recognize rejection symptoms, plan proper diets and generally take responsibility for your recovery at home. The transplant coordinator, social worker, and psychiatrist are all available when needed. The social worker will help arrange your discharge needs, such as rehabilitation or long-term placement, chemical dependency counseling, and transportation home. You’ll also be offered a referral to a community health nurse who can help you at home.

Long-term Management and Life After a Transplant

After you leave the hospital, you’ll return on a regular schedule for follow-up visits. A medical team will follow your progress throughout your life. You’ll have regular blood tests to make sure that your new kidney is not being damaged by rejection, infections, or other problems. Over time, both the frequency of lab tests and the doses of medicine are reduced.

You’ll need to eat a healthy diet and exercise and use medicines, including ones you can buy without a prescription, only if your doctor says they’re safe for you. If you’ve been on hemodialysis, you’ll find that your post-transplant diet is much less restrictive. You can drink more fluids and eat many of the fruits and vegetables you were previously told to avoid. You may even need to gain a little weight, but be careful not to gain too much weight too quickly and avoid salty foods that can lead to high blood pressure. It’s important to work with our dietitian to make sure you’re following a healthy eating plan and to follow your doctor’s advice to take care of your new kidney.

Returning to Normal Activities

After a successful kidney transplant, most people can go back to their normal daily activities. Getting your strength back will take some time, though, depending on how sick you were before the transplant. You’ll need to check with your transplant team on how long your recovery period should be. Social workers and support groups will help you adjust to life with a new kidney.

Eventually, though, you’ll be able to return to work, engage in normal exercise, and return to a normal sex life. However, women should avoid becoming pregnant during the first year after a transplant. It’s best to consult with your doctors about sex and pregnancy.

Here is an example of a typical kidney transplant patient encounter:

Dr. Barry: Good morning. Your Nephrologist has referred you to our center for evaluation of your kidney transplant surgical candidacy. I understand that the cause of your end stage renal disease is Diabetes Mellitus Type II and that you are not yet on dialysis.

Pt: yes, that’s correct.

Dr. Barry: Do you have any friends or family members that are interested in donating a kidney to you?

Pt: I’m not sure. How does one become a donor?

Dr. Barry: Living donor kidney donation involves identifying a family member or an emotionally related donor (e.g., spouse or good friend) who has a compatible blood type with the recipient, is in good health and has no risk of kidney problems in the future such as diabetes or high blood pressure. If a donor is identified who meets these initial criteria, he or she will then undergo an extensive psychosocial evaluation, physical exam, laboratory tests including more detailed screens for immunologic compatibility and imaging tests (X rays and MRI scan) to assure normal anatomy and absence of intrinsic kidney disease.

Pt: What is the risk to the donor?

Dr. Barry: If the donor passes our rigorous screening procedures, then we will arrange for a simultaneous surgical procedure in which the donor’s kidney is removed and immediately transplanted into the recipient. We almost always perform the donor surgery laparoscopically, using small incisions, and the patient stays in the hospital for two to three days. The risks include adverse reactions to general anesthesia, bleeding, infection and possible conversion from a laparoscopic to open procedure. These risks are minimal and the chances of having to perform an open procedure are less than 1%.

You can watch a video of a laparoscopic kidney removal (“nephrectomy”) here.

Pt: What are the advantages of living donor kidney transplant?

Dr. Barry: The main benefit is that we can perform the transplant within months of identifying a suitable donor. The waiting time for a deceased donor transplant (formerly called cadaveric transplant) is 4 to 5 years here in our region. Also, living donor kidneys are more likely to function immediately, lessening the likelihood of the recipient needing temporary dialysis after the transplant. Finally, living donor kidney transplant recipients enjoy better long term graft survival.

Pt: Can I have a transplant before going on dialysis?

Dr. Barry: Yes, but if your kidney function is not too bad, we need to wait until you are closer to needing dialysis. If we perform a transplant too soon, the benefits of receiving a new kidney are cancelled out. We measure your creatinine and creatinine clearance to help us decide the optimal timing of your transplant before going on dialysis.

Pt: Will you remove my own kidneys during the transplant?

Dr. Barry: Usually we don’t have to do this. However, if you have a kidney disease that causes ongoing problems, for example, multiple blood transfusions, persistent kidney infections or intestinal blockage, then we would consider removing your own kidneys. The two most common medical conditions requiring “native nephrectomy” (removal of your own kidneys) are Congenital Reflux Disease and Polycystic Kidney Disease. If you have these diseases, we would decide based on your symptoms or complications whether you would need to have your kidneys removed.

Pt: If I needed to have my own kidneys removed, when would you do this?

Dr. Barry: My practice is to remove the native kidneys at the time of transplantation. This requires a slightly longer stay in the hospital because the surgical incision (cut) is bigger, but the benefit is that the patient only has to undergo one surgical procedure and one general anesthetic. Occasionally, we will perform the removal of your own kidneys prior to the transplant in a separate procedure.

Pt: Getting back to living donor kidney transplantation, what if I have no friends or family members who can donate, or what if I am uncomfortable about asking anyone to do this?

Dr. Barry: That’s perfectly fine. It’s especially important to realize that if you are uncomfortable about asking anyone to donate, then you shouldn’t do so. Organ donation is a gift and it should come from the heart, not by emotional coercion. Financial coercion for organ donation is illegal in the United States.

If you are on the deceased donor kidney transplant list, the waiting time can be up to 3-4 years. We do have a voluntary program, the “Extended Criteria Donor (ECD) Program”, that allows people on the list to wait for less time (2-3 years) if they are willing to accept kidneys that are slightly outside our normal criteria for acceptance.

Pt: What exactly do you mean by this?

Dr. Barry: Normally, when a donor becomes available, the surgeon is called to accept the organ. If the patient is older, has had diabetes or high blood pressure or has had a stroke, then the surgeon may not think that this is the best organ. But, if the donor is not too old and has not had diabetes or hypertension for a long time, we will perform additional tests on the kidney, including a biopsy, to determine if the kidney will work. We then offer this organ to our recipient patients participating in the ECD program. It is completely voluntary and if the patient does not want to accept the ECD organ, he or she will not be penalized in terms of their listing status. Patients participating in the ECD program are also on the “regular” list and they always have the option to choose between either types of organ.

Pt: What is the surgery like?

Dr. Barry: The kidney transplant operation is a straightforward procedure. The surgery takes about two hours and starts with an incision (usually about 6 to 8 inches) from your pubic bone up to your hip bone. We place the new kidney in your pelvis and connect it to the blood vessels in your groin as well as connecting the kidney to your bladder.

Pt: How long do I stay in the hospital?

Dr. Barry: Most people stay five days.

Pt: What are the potential complications?

Dr. Barry: Complications for this surgery are rare, but include adverse reactions to the general anesthetic medicines, bleeding, infection, blood clots in the artery or vein going to the kidney, twisting or “kinking” of these blood vessels, a leak of urine where we connect the kidney to the bladder, a narrowing of the connection to the bladder, or a fluid collection around the kidney after the surgery, usually either blood or lymphatic fluid.

Pt: What happens if I get one of these complications?

Dr. Barry: Often, they can be treated without surgery, but sometimes another surgery is required. For example, problems with the blood vessels, leaking of urine or a collection of lymphatic fluid all may need an additional surgery to fix definitively. We rarely have to perform a second surgery, but they are usually minor procedures and most always result in a complete resolution of the problem.

Pt: Does the new kidney start working right away?

Dr. Barry: Usually it does, but sometimes the new kidney is “stunned” or “sleepy” and it doesn’t start working immediately. This is more common with deceased donor kidney transplants but can, very rarely, happen even with living donor kidney transplants.

Pt: What happens if my new kidney is “sleepy”?

Dr. Barry: Sometimes patients will require dialysis after their transplant operation until the kidney starts working. If it is a simple matter of delayed kidney function (that is, if there are no technical or surgical complications and there is no rejection), then kidney will most always “wake up”. In these cases, the need for dialysis can last anywhere from a few days to a few weeks.

Pt: What about rejection?

Dr. Barry: You will have to take anti-rejection medicines every day after you receive your kidney transplant. These days, our medicines are so effective in preventing and treating rejection that it’s extremely unusual for someone to lose their kidney because of rejection in the first several years after transplant. Nonetheless, about 20% of all kidney transplant recipients experience an episode of rejection in the first few years.

Pt: How can I tell if I am experiencing rejection?

Dr. Barry: Usually, there are no symptoms, but occasionally patients have tenderness over their new kidney, fevers or decreased urine output. More commonly, you will be feeling fine and we detect an abnormally elevated creatinine level on your routine blood tests. First we will make sure that your anti-rejection drug levels are not too high, that you do not have a urinary tract infection and that you have been keeping yourself well hydrated: all of these things can cause the creatinine to be elevated. Then, we will perform an ultrasound of your new kidney to make sure that there are no technical problems such as blood clots in the kidney, problems with the connection to the bladder, or fluid collections around the kidney. If the ultrasound is normal, then we will perform a biopsy of your kidney.

Pt: Is that another operation?

Dr. Barry: No. A biopsy is performed by placing a small needle through the skin after numbing the skin with local anesthesia. It can be performed as an outpatient procedure.

Pt: What if the biopsy shows rejection?

Dr. Barry: Depending on the type of rejection and the degree of rejection, we will treat you with the appropriate anti-rejection medicine. If the rejection is mild, we will give you intravenous steroids for two or three days. If it is more severe, then we will use more powerful antibody medicines for up to five days. These treatments almost always completely reverse the rejection. So, as long as we catch the rejection in a timely fashion, losing the new kidney would be a very rare occurrence.

Pt: What are the risks of taking anti-rejection medicines

Dr. Barry: In general, there are risks of certain types of infection and certain types of cancer. In the first three months, your risk for infections is highest, so we give you medicines to prevent certain types of bacterial, viral and fungal infections. After three months, we stop these prophylactic medicines and keep your anti-rejection medicines going at reduced doses. The risks for cancer, particularly skin cancer and lymph node cancer, is slightly higher than the general population. We recommend that you avoid prolonged sun exposure and that you always use appropriate protection from the sun. Regular routine physical exams and blood tests are important for early detection of cancer.

Pt: Do the anti-rejection medicines have any other side effects?

Dr. Barry: Ironically, one of the major side effects of Cyclosporine and tacrolimus is kidney toxicity. We are able to avoid this by regularly checking the levels of these drugs in your blood and adjusting your doses appropriately. Cellcept, another anti-rejection medicine, can cause stomach upset, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. Sometimes we have to lower the dose of this medicine or substitute another very similar drug that is less likely to have these side effects. Finally, steroids can have many die effects such as diabetes, growth delay in children, osteoporosis, facial and skin changes, or neurologic problems such as difficulty sleeping or euphoria. However, we are very aggressive about rapidly decreasing your steroid dose over a period of several weeks after your transplant, so that many of these potential problems are avoided. Many patients have to take insulin shots after their transplant, but often the need for insulin shots eventually goes away as the steroid dose is lowered.

That essentially covers all that you need to know about your kidney transplant operation. Do you have any other questions?

Pt: Not at the moment, but I’ll contact you if I do. Thank you very much for your time.

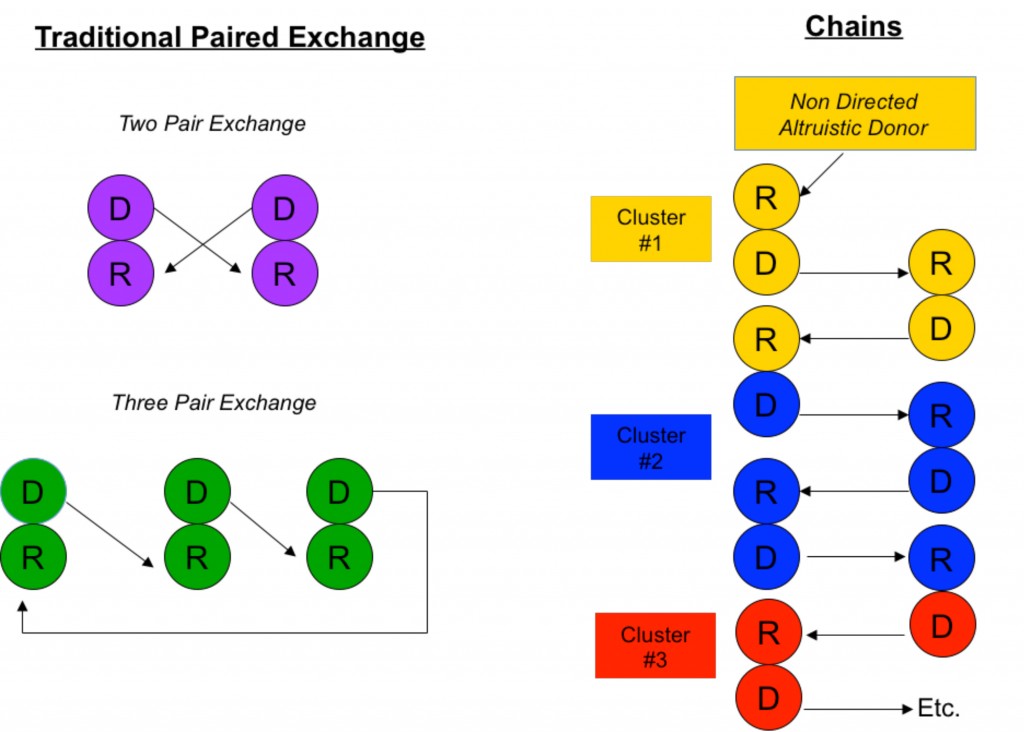

Paired Donor Exchange and Non Directed Donation for Kidney Transplantation

Paired donor exchange involves two kidney recipients exchanging their intended donors with one another. If a donor has an incompatible blood type or has antigens to the recipient, they can instead donate to another unknown, but compatible, recipient in exchange for that recipient’s donor. In this way both donors can provide healthy kidneys to both recipients when transplant would have previously not been possible. A non directed kidney donation “chain” begins with an altruistic donor donating a kidney to an incompatible pair, and the donor from that pair passes his or her kidney on to another recipient or incompatible pair. I will briefly describe the basis of “matching” in kidney transplantation, and then describe paired donor exchange and non directed donation in more detail.

A successful kidney transplant requires first and foremost an appropriate “match” between the donor and recipient. In the matching process, we consider ABO blood type compatibility, Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) tissue types of the donor and recipient, and whether or not the recipient has antibodies against the donor (usually in the form of anti-HLA antibodies). We identify six HLAs that are most predictive of rejection to determine the degree of tissue typing match between donor and recipient. A “perfect match” is when all six HLAs are the same. This happens with identical twins, in siblings 25% of the time, and very rarely between two unrelated individuals. Perfect match kidneys last longer and the recipients require less term immunosuppression.

Currently, our standard immunosuppressive drugs are so good that it is unusual for a recipient to lose one’s kidney due to rejection in the first several years from transplant. The drugs are quite effective in preventing a severe rejection and even if some rejection occurs, there are even stronger medicines available to completely reverse the process. So nowadays, a good match simply means a compatible blood type and the absence of antibodies in the recipient’s blood directed against the donor’s tissues (or “antigens”). This is especially true with living kidney donation, where recipients do not even have to be related to their donors (e.g., husband to wife, friend to friend) to enjoy excellent outcomes.

We can, however, develop antibodies to HLAs. This is called “sensitization” and can occur as a result of multiple pregnancies, multiple blood transfusions, or previous transplantation. The presence of specific antibodies in a recipient to a particular donor’s HLAs is detected by a crossmatch assay. If the crossmatch assay is positive, the likelihood of immediate rejection is high. People who are highly sensitized have antibodies to many different HLAs and are therefore difficult to transplant.

So what happens when a sensitized patient wants to receive a living donor kidney transplant from a friend or loved one, but they are either the wrong blood type or crossmatch positive? Here at the University of Rochester, we have protocols to reduce the amount of ABO antibodies or HLA antibodies. These programs are state of the art and involve highly sophisticated treatments and medications. Very often they are successful in allowing transplants between ABO incompatible pairs or crossmatch positive pairs. They are not successful 100% of the time in reducing the antibodies, however, and sometimes we can not proceed with the transplant.

There are alternative approaches that are complementary to pharmacologic desensitization. Paired donor exchange and non directed donation involve the sharing of organs between pools of donors and recipients to achieve combinations that obviate existing ABO mismatch and HLA sensitization barriers.

The simplest scenario of a paired donor exchange (see Figure “Two Pair Exchange”) is one where a donor pair is ABO incompatible (say Jane, who is blood type A, wants to donate to Joe, who is blood type B) but complementary with another ABO incompatible pair (Frank, blood type B, wants to donate to Gertrude, blood type A). Well, why not have Jane donate to Gertrude (A to A) and Frank to Joe (B to B)? Even if Jane and Joe don’t know Frank and Gertrude, this scenario is ethical because all are benefiting. It is also medically simpler because no fancy immune system manipulations are necessary other than standard immunosuppression.

Paired donor exchange can be expanded to three pairs, allowing the exchange of crossmatch positive pairs with crossmatch negative pairs (see Figure “Three Pair Exchange”).

Another similar approach is to perform non directed “chain” donations (see Figure “Chains”). Chains, by necessity, always start with an altruistic, or “Good Samaritan”, donor who wishes to donate his kidney out of the goodness of his or her heart to a complete stranger. (People like this do exist in this world.) Through a sophisticated computer algorithm, a virtual crossmatch chain is set up to maximize the amount of potential crossmatch negative transplants among a large pool of recipients.

As you can imagine, this endeavor can quickly become logistically complicated. In a simple paired donor exchange performed at a single hospital, four separate surgical teams and four operating rooms need to be available simultaneously. Such a scenario is possible only in the most dedicated and larger transplant centers such as the University of Rochester. In order for non directed donation chains to be of maximum benefit, the pool of participating donors and recipients must be large, and multiple transplant centers must be involved. Usually, simultaneous surgeries are performed at different hospitals and, sometimes, transcontinental exchanges are necessary.

Safeguards to ensure fair exchanges are critical. These include performing the donor surgeries at the same time to prevent a donor from backing out and leaving a recipient without an organ. This is also the case with the transplant operations. Furthermore, the donor/recipient pairs remain anonymous prior to transplant to prevent any coercion on the donors.

Ethical considerations are paramount. For the healthy donor undergoing the risks of surgery to help someone else, we must do everything possible to ensure that the outcome has a high likelihood of success. Recipients benefitting from this strategy should be those most in need, for example, highly sensitized patients. Finally, society as a whole must benefit. Non directed donations and paired exchanges do not disadvantage patients on the deceased donor waiting list because donor kidneys do not come from the pool utilized by those on the list, and chain donations are usually terminated by a donation to the highest person on the deceased donor waiting list.

In this country, the fastest growing source of kidneys is from live donors. Several hundred kidneys have been transplanted over the past several years using paired donor exchange and non directed donation strategies. Combining these strategies with pharmacologic desensitization protocols allows even more people to be transplanted because they increase the chances of finding a donor with a low level crossmatch more amenable to successful desensitization. Every time someone is transplanted using a live donor, one less person is added to the deceased donor waiting list.

Here at the University of Rochester, we are beginning to participate in a kidney donor exchange network encompassing more than 80 other transplant centers. We also have well established state of the art protocols to pharmacologically desensitize highly sensitized patients. Combining these modalities allows more people to be transplanted and maximizes the probability of achieving the best possible outcomes.